(See the original interview at www.literaturemonthly.com)

They are both Americans, both highly-literary: Payne is the author of five novels that take place in Europe and follow the lives of itinerant dreamers who wander the world in search of adventure, meaning, and the “poetic life.” Like his characters, Payne, 38, is an itinerant dreamer who lives in Paris, wanders in Europe, and devotes his time to “living the Homeric life,” and “inventing the next novel.” Payne and Maneos are both published by Aesthete Press.

Above, Left: Roman Payne (Photo, copyright 2014: Marta Szczesniak, Photography) | Above, Right: Pietros Maneos. NOTE: SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THE ARTICLE FOR FULL-SIZED PHOTOS OF THE AUTHORS.

Maneos, 35, is no less a son of the divine Homer. He seeks aesthetic perfection in all things: his life, his Ancient Greek body, and his literature, which, like Payne’s, marries Classicism and Romanticism. Unlike other professional authors who seek the cliché in mid-life of some kind of professorship at a university, or a pay check in exchange for scholary pursuits in a library, Maneos chose a life that few have managed to live since the decline of the Ancient Roman aristocracy: he purchased 40-acres of Eden in North Carolina where he is constructing a vineyard to live his own version of a life like one of his heroes: the Roman literary-patron Gaius Maecenas. “Bramabella” is the name that Maneos chose for his vineyard—a construction of two Italian words that, assembled, mean “yearning for beauty.”

The two authors and the editor Jean Sitori are sitting in the office of the newspaper Literature Monthly in Paris. Jean is entranced as he watches Maneos stand and demonstrate how to properly hurl the discus. After a moment, Jean turns his attention to Payne…

JEAN SITORI: Roman, speaking of hurling the discus, you just got back from Greece where you were living for about four months… Are you happy to be back in France? Were you writing well in Greece?

PAYNE: I am always happy to be back in France—that is why I almost never leave France to begin with. When I get tricked into leaving France, I almost always regret it afterwards. I initially went to Greece this trip to research my next novel at a place on the beach just outside of Athens. But the weather got bad, the sea turned cold and violent—fault of Poseidon! I can deal with nasty weather. But when the inspiration to write disappears, I lose my mind. Here I was in Greece: the birthplace of the muses, and they had abandoned me. I tried all the tricks to get literary inspiration back: yoga, running, hard alcohol, nothing worked. My thoughts were so black that I became convinced that writing was something that was no longer a part of me at all. Now, back in France, I suddenly feel like writing again; and my work is going well.

JS: Are you reading at present?

PAYNE: No. When I am writing well, I do not read. Reading takes valuable time away, and it puts another man’s or woman’s style in your head to mar your own. What are you reading at present, Jean?

Jean makes a wholehearted laugh at this and says, “Let’s see… what am I reading these days?” With that, he begins leafing through a copy of the woman’s magazine Grazia, which he said, had “mysteriously” appeared in his briefcase that day. After scanning a blonde woman smoking a cigar for a moment, his eyes light up. He’d found an article worth commenting on to his guests. Jean summarized the article…

Facebook’s founder Mark Zuckerberg told Grazia that he made it his 2015 New Year’s resolution to, quote, “read more literature,” and to finish a book every two weeks. This resolution, he said, inspired him to make reading “chic” (we didn’t know that Zuckerberg had a magic wand for making things chic, but why not?!), so he has created a Facebook page called “A Year of Books.” It currently has just over 350,000 likes.

JS: Pietros, what do you think of Zuckerberg’ public display of affection for reading?

MANEOS: Well, I think that it is noble of Mr. Zuckerberg to do so, especially as the head of a technology company, since society seems to be awhirl over technological platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Vine and others, which has perhaps led to a decline in the written word. Not that there aren’t a plethora of authors flooding the marketplace, but it seems that modern man has lost the ability to sit quietly with a book for an extended period of time without succumbing to the lure of online ephemera’

JS: Some of the books Zuckerberg said he is reading are excellent titles. Perhaps his publicist thought them up to make the Facebook founder seem complex and interesting, or perhaps he really is interesting. Anyway, many of the titles delve into the Baroque, others into Romanticism, others into Ornate Gothic Style… since your own books are complex and ornate, and explore Baroque Romanticism, do you foresee that pop-culture is going to lean more in your direction and away from current trends, like Philip Roth ?

MANEOS: Well, I think popular culture and literary culture are two disparate entities. With regard to popular culture, I think that it is enamored with ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ and other such works, no?

But now transitioning to literary culture, I don’t think that there has been much cultural shift from the irony, cynicism, and anti-aestheticism of the previous epoch. I still think that many writers and artists are busy declaiming ‘Isn’t it pretty to think so?’, while writing in short, spare, suburban sentences. I, of course, have rejected this trend for a Baroque aestheticism that one finds in personages like D’Annunzio and Kazantzakis. I embrace epithet, adjective, apposition and heightened musicality, which are despised by many moderns. So, I certainly consider myself part of a burgeoning counter-culture of To Kalon in modernity along with such movements in the visual arts such as Post-Contemporary.

JS: Pietros, just what is it about “Baroque aestheticism” that you embrace? And can you explain the term a little for our readers who have turned a blind eye to that phrase up until now?

MANEOS: An example of Baroque aestheticism might be, ‘The light, soft and sensuous, brushed across the crest of the Brushy Mountain,’ where spare, suburban 20th century minimalism would simply say, ‘The light hit the Brushy Mountain.’

The great Matthew Arnold once noted, ”The instinct for beauty is served by Greek literature and art as it is served by no other literature and art,’ and I am striving to continue this Hellenic sensibility in the 21st century.

JS: Pietros, when one reads your work; or talks to you personally, and listens to your music playlists, one feels that you are more Greek than any full-blood Greek currently alive in Athens, or in Sparta, or Macedonia… How come you didn’t start Bramabella in Greece instead of America? Or at least, why don’t you live six months of the year in North Carolina, and six months of the year in Greece?

MANEOS: Well, although I am Greek by descent and sensibility as an ardent student of classical antiquity, I do not speak demotic Greek, so that alone would be a challenge. Additionally, Greece is suffering under dire economic conditions, so if I ventured there, I might end up starving to death, ha!

Also, similarly to the orator/philosopher Isocrates, I have always believed that Greece or rather Hellenism is not so much of a language, or a land-mass as it is a world-view, a philosophy, if you will. Figures like Oscar Wilde, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, Paul Cartledge, John Boardman and many other Artist/Scholars are as Hellenic as any Greek whose last name happens to end in ‘os’ by happenstance. You too, my friend, are Hellenic even though you were born in America, and have elected to reside abroad.

Though, I must make a final confession to you – Traveling to Greece to raise a classicizing army to battle ISIL in Syria-Iraq does intrigue me, as it is perfumed with both Herakleanism and Byronism.

JS: Pietros, our poor friend Roman is starting to daydream over there in his chair—one can tell because his eyes look like Lucy in the Heavens with Rhinestones—maybe he is bored because we are so interested in your work right now. To ask you a question about Roman’s work… His first novel was a Parisian thriller in the Dostoevsky style. His second, Cities and Countries, was a Bildungsroman set in an imaginary world. His third was a tragic love story. His fourth was a diary of seducing women in Paris—everyone from impoverished seamstresses without breeding and a ripe age that can be counted on three hands, to blue-blooded countesses cheating on their husbands. Then his fifth novel, “The Wanderess,” well that is more hard to define. The question is… you, Pietros, are a literary scholar and, if I may flatter you by saying: a literary visionary. What do you think Roman’s sixth novel will be about? What do you think it “should” be about?

MANEOS: Roman is a great genius, and I think that for Rooftop Soliloquy and The Wanderess he should be considered for the Nobel Prize, but to speak of your question, I think that he should continue in the Heroic and Aesthetic vein. Perhaps, since he is descended from the ‘Chian Nightingale’ – Homer – in such a pronounced way, he could write a Modern Odyssey akin to what Kazantzakis attempted.

JS: You make the distinction between two phrases: ‘The light hit the Brushy Mountain,’ and one that I believe you appreciate more: ‘The light, soft and sensuous, brushed across the crest of the Brushy Mountain.’ …Mark Zuckerberg would probably claim to agree with your tastes. Do you think this is an anomaly—the preference of a well-educated billionaire matching the preference of a Homeric poet who is most likely a descendant of the immortal poet Sappho ? Or do you think that we may be entering a new literary age—a time when people are, frankly, sick and tired of “spare, suburban, 20th Century minimalism?”

MANEOS: Well, I am not sure about a new literary age, but one can only hope! I think that my kinship with figures like Roman Payne, Tomasz Rut, Michael Newberry, Sabin Howard, Graydon Parrish, Michael Imber and others is indicative of a cultural paradigm shift. I am always hesitant to use the term ‘movement’ – but – there is certainly a shared sense of aesthetic values. And one of my aims is to have Bramabella stand as an expression of this aesthetic.

JS to PAYNE: Pietros Maneos is a poet, novella scribe, and satirist… he is a writer of many styles, many genres. What is your favorite genre of his at present?

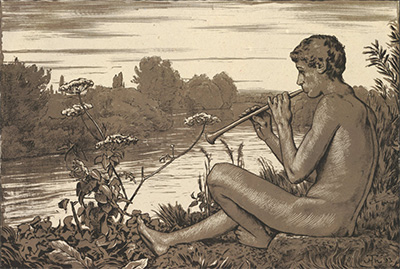

PAYNE: Maneos has arrived at a sacred mastery of certain literary forms (I am not fond of the word “genre”). I would say, these “sacred forms” are my favorites of his, since no one does them better than he does. The forms that come to my mind first is what I would call his “Bramabella Pastorales.” In these poems, Maneos is able paint a landscape like Renoir or Monet, construct a exquisite virgin like John Williams Waterhouse, sing of the youthful love of a troubadour, or the old man’s lament of a Cavafy poem. He can prepare the body to fight like a Homeric hero, fall to tears like a Nocturne of Chopin. They are all that is life: his Bramabella poems are the laments of a poet intoxicated with wine, and the joys of a madman sipping the sweet fumes of the poppy.

JS: And what is the literary style that you would like to see Maneos work on next?

PAYNE: I would love to see him write a 200 page “roman d’amour” in the French tradition… an old style novel about a couple’s first love, and their last.

JS: (To the readers)… This concludes our all-too-short interview, but we at Literature Monthly hope to have Maneos and Payne with us again soon!